The statistical indicators headed into the holiday weekend were pretty good, overall, but our hospital capacity cushion remains small (especially in Wichita), so hopefully we won't see much of a post-holiday surge of new cases. Already, many more Kansans are without their loved ones this year. We recorded another 500 deaths in the last two weeks, topping 2,500 just before Christmas. We've been averaging 40 to 50 COVID-19 deaths every day in Kansas lately. And that probably won't slow down markedly for another week or two, because deaths are a lagging indicator.

Saturday, December 26, 2020

Kansas COVID-19 Update, Week 24

Saturday, December 19, 2020

Kansas COVID-19 Update, Week 23

We have reached a bit of a plateau in Kansas: hospitals remain pretty full and the COVID death rate remains dispiritingly high, but things are neither getting rapidly worse, like they are in California (where new cases rose 120% between Dec. 3 and Dec. 17, as compared to the previous two weeks), or steadily better, like they are in Minnesota (where new cases fell by 31% over that time). The rate of new cases in Kansas has flattened out, but it's still near the highest level it's been throughout the entire pandemic. Which makes us vulnerable to a big surge around special events, like Christmas or New Year's, if too many people gather and spread the virus around. Or, we could hunker down for a few weeks more and really turn this thing around so dozens of Kansans aren't dying every day with a vaccine that could have saved them in sight.

The Good: The infection reproduction rate, or Rt, dropped to 0.97. That's the lowest it's been since May and it's excellent news because it means that if we limit the virus to its current rate of spread (by wearing masks, social distancing, washing hands, avoiding large gatherings, etc.), we will not just flatten the curve, but bend it down.

The Bad: Hospitals have yet to really feel much relief. ICU capacity in Kansas was about 18% as of Dec. 18, according to the Kansas Hospital Association. We'd like to get that above 20% to really feel like everybody can get the type of care that will give them the best chance to survive. As mentioned in prior weeks, the capacity is not evenly distributed. Just 7% of ICU beds were available in south-central Kansas, which is largely because Wichita's hospitals remained at capacity for the seventh straight week. While new cases are finally declining in the western third of the state, the center of the state remains red-hot (see heat map below), which will continue to strain ICUs in Wichita, Salina and Hays.

The Ugly: Test positivity was largely unchanged, at a ghastly 37.7% this week, according to Johns Hopkins. That's fifth worst in the country behind Idaho, South Dakota, Alabama and Pennsylvania. We haven't tested enough since the beginning of the pandemic, and we still aren't testing enough. At the beginning we just didn't have the capacity to test enough, but now I think we do. I'm guessing some of our shortfalls now stem from geographic challenges (it's a long drive to a testing site in some parts of the state) and COVID fatigue (people with a known exposure or mild symptoms who might have previously gotten tested are now just kind of over it and will wait and see if they get sick). Consequently, a high percentage of the people who are getting tested are probably acutely ill, and therefore more likely to test positive.

Bonus: Here's a striking statistic for you: Nemaha County, along the northern border of Kansas, has about 10,000 people in it. Douglas County, where Lawrence is located, has about 122,000. Yet more people have died of COVID-19 in Nemaha County (43), than in Douglas County (31). In fact, Douglas County has one of the state's lowest COVID death rates, per capita, despite tens of thousands of college students moving in and out of Lawrence (and partying) during the pandemic. Douglas County has had a mask mandate since June; steady, consistent messaging about masks, social distancing and hand hygiene; lots of testing (both on the KU campus and off); and a willingness to close bars and limit gatherings when community spread is high. Some people think those interventions don't make any difference. I think they do. If Douglas County were merely at the state average for COVID deaths (about 80 per 100,000 people), close to 100 residents there would have died of COVID now. Douglas County's response to the pandemic has probably saved 60 to 70 lives.

Saturday, December 12, 2020

Kansas COVID-19 Update, Week 22

The Good: The infection reproduction rate, or Rt, dropped to 1.01 last week. That's a good number that suggests the Thanksgiving surge could be short. We're almost to the point where cases would start to decline. We desperately need an extended period of declining cases.

The Bad: ICU capacity remains stubbornly low, at 17% statewide as of Dec. 11, according to the Kansas Hospital Association. That's about the same as last week, and persistently full ICUs are likely playing a role in the large number of deaths. Some of the Kansans in those beds probably would have survived if we hadn't spread our medical system so thin.

The Ugly: Test positivity was 37.1% in Kansas this week, according to Johns Hopkins. That's better than the week before, but still awful. It's the fourth-worst rate in the country, behind Idaho, South Dakota and Pennsylvania.

Bonus: When the pandemic first came to Kansas it came mostly to the urban areas. But for the last few months it's been overwhelmingly a more rural disease — so much so that the rural parts of the state have now borne a much greater overall disease burden than the urban parts. In past weeks I've occasionally shared a "heat map" that shows which areas of the state are recording the most NEW cases per capita. That's useful because it tells you where the virus is spreading right now. But here's a map that shows which counties have recorded the most CUMULATIVE cases per capita, going all the way back to the beginning of the pandemic.

It's striking, isn't it? You can see that the pandemic has hit hard in Wyandotte County, but nearly every other "deep red" county is rural. The coronavirus has ravaged basically the entire western third of the state, and many of those cases have come in just the last few months. Early on in the pandemic, that part of the state was largely COVID-free, except for some outbreaks in meat packing plants, prisons and nursing homes, where chains of infection were easy to identify and contain. But in the last few months that part of the state has witnessed persistent, out-of-control community spread.

It's had devastating consequences for a lot of families out there, too. Here's another heat map, this one depicting cumulative COVID deaths per capita since the beginning of the pandemic.

As a proportion of their population, rural counties have now become much more acquainted with death-due-to-COVID than their urban counterparts. In fact, tiny Gove County, Kansas (population 2,600), has had more COVID deaths per capita than anywhere else in the country. And yet, those counties are much less likely to require residents to wear masks. Gove County's government approved a mask mandate in August, but then repealed it almost immediately amid intense anger from locals (someone apparently even threatened to blow up one county commissioner's house). Even in rural places where masks are technically required, like Dodge City, resistance to wearing them remains high. It is sad, but I'm not sure what it will take to get those attitudes to change. An awful lot of death in a relatively short period of time hasn't done it yet.

Saturday, December 5, 2020

Kansas COVID-19 Update, Week 21

After a brief dip in new cases, COVID-19 is once again on the march in the Kansas City area and the state of Kansas. We are experiencing the predicted Thanksgiving surge (following the incubation period), and can expect another week or two of increasing infections until they hopefully start to level off and go down again. Then we'll have to deal with the Christmas surge. No good news in the data this week.

The Bad: The infection reproduction rate, Rt, ticked up from 1.05 to 1.07. That means each infection now causes, on average, 1.07 more. So while it may not look like a huge jump, it translates to a LOT more infections because we're starting from like 3,000 per day. We really need this number under 1.0. But Thanksgiving gatherings made an increase predictable. Hopefully it's temporary.

The Worse: ICU capacity fell from 21% last week to 16% on December 4, according to the Kansas Hospital Association. After a brief respite, we're back down to where we were two weeks ago. The Wichita area continues to be particularly strained, with just 5% of ICU beds remaining. And remember, Wichita's hospitals have already put in place their "surge" protocols and added extra ICU beds. They've been above their normal ICU capacity for more than a month. Now they're also bumping up against their surge capacity. It's a very difficult time to be a hospital worker or a patient in Wichita.

The Ugly: Test positivity in the state rose from 38.1% to 46.6%, according to Johns Hopkins. That's third-worst in the country behind Idaho and South Dakota. It's a terrible number and it suggests that new infections are rising even faster than we currently think they are because many are going unidentified.

Bonus: I don't know what more can be done to convince people to wear masks, or to convince political leaders to require masks. We now have much better mask coverage in Kansas than we did just a month ago, thanks to Gov. Kelly's second mask order. But there are still dozens of mask-free counties in the state. Many of them are in western Kansas. Here's an updated heat map that shows where the most new cases, per capita, are being recorded.

To be clear, the yellow and orange counties aren't great. We could use more greens. But look where all the red is. Those counties are major COVID incubators. That affects the whole state, because the virus doesn't respect county lines and hospital patients are routinely transferred across county lines. Hays Medical Center's medical director said this week that nearly all of her hospital's COVID-19 cases come from counties that don't require masks.

I get that all counties are different and I'm a fan of local control for a lot of things. But viral pandemics aren't one of them. Ideally we should have a cohesive national strategy for containing COVID-19, but in the absence of that we should at least have a cohesive statewide strategy, especially given that the coronavirus is now endemic in every region of the state. The county-by-county patchwork approach is making things worse.

A binding statewide mask mandate would still help. In North Dakota, Gov. Doug Burgum instituted one on Nov. 13, after months of resistance. A Carnegie Mellon survey of Facebook users showed that the percentage of North Dakotans who reported wearing a mask rose to almost 90% after Burgum's order (it had been under 70% about a month earlier). Active COVID-19 infections have been cut almost in half there since the order.

Saturday, November 28, 2020

Kansas COVID-19 Update, Week 20

The "grim milestones" are coming faster now. It took six months (from March 11 to Sept 11) for Kansas to reach 500 COVID-19 deaths. It took about six weeks (from Sept. 12 to Oct. 28) to record another 500. Then four weeks (from Oct. 29 to Nov. 23) to record yet another 500. Given the current ICU numbers, the state's death rate is not likely to slow in the near future. It's more likely to accelerate. Which means we'll probably hit 2,000 COVID deaths by Christmas.

The Good: The infection reproduction rate, or Rt, fell from 1.06 to 1.05. We could really use a bigger drop than that, given where we're at with hospitalizations. But we moved closer to the magic number of 1.0, so that's good. We're already seeing new cases taper off in parts of the state that put new infection control measures in place, like the Wichita area and Kansas City area.

The Bad: ICU capacity improved a bit, going from 16% availability to 21%, according to the Kansas Hospital Association. But there are still very worrisome trends underneath those numbers. ICU capacity remains totally tapped out in southwest Kansas, and nearly tapped out in south central Kansas, which is no surprise given that Wichita's big ICUs have been over capacity for a full month now. And the state has 292 COVID-19 patients in ICU, which is yet another record. Which means the new capacity is from adding ICU beds and having fewer non-COVID patients. We can't count on that going forward.

The Ugly: Test positivity went up, from 35.1% to 38.1%, according to Johns Hopkins. Not as high as it was two weeks ago, but still way too high and now trending the wrong direction. This means we're missing more infections than we were the week before — and we've been missing far too many infections for months now.

Bonus: Gov. Kelly's decision to issue a second mask mandate appears to have paid off. This time, most counties didn't vote to opt out. More than half of the counties in Kansas (about 70 out of 105) now require masks. This was a pleasant surprise for me. I expected more of the local officials in rural areas to buck the governor's order, given the politics of the situation. But this gives me hope that masks aren't as politicized as I thought (although it should be noted that county commissioners voted to opt out again in some of the areas of SW Kansas hardest hit by COVID-19, like Ford County and Seward County, which is mind-boggling).

The new mask rules also give me hope that we might see new daily cases start to decline statewide in about 10 days (after the incubation period), which would then results in fewer hospitalizations in about two weeks. The big wild card in all this, though, is Thanksgiving. If too many people decided to ignore public health recommendations and gather together in person, then we will likely see a spike in the next two weeks, rather than a decline, even with the new mask order. Either way, the death rate is likely to march on dispiritingly in the short term. Many of those 292 Kansans currently in ICU with COVID are not going to make it.

Saturday, November 21, 2020

Kansas COVID-19 Update, Week 19

We're entering the bad times now. The days of overflowing hospitals and overburdened health care workers that first plagued Wuhan, then northern Italy and then New York City are now coming to Kansas, as unlikely as that once seemed. Wichita's ICUs are over capacity (231 patients as of Nov. 16, vs. a capacity of 208). Topeka's hospitals reached capacity last week and started boarding patients in hallways. They've now requested staffing help from the National Guard and FEMA. The Kansas City region still has some ICU capacity, but it's going fast, hovering between 10% and 20% availability most days. And it's harder to staff those beds because health care professionals are getting COVID too.

All of which means delays in care and preventable deaths – for Kansans with COVID-19 and other conditions — for the foreseeable future. There are some signs that maybe new cases are finally leveling off in the KC area, but they're plateauing too high to be sustainable. And exponential growth in new cases continues in the western half of the state. The next few weeks are baked in, they will be bad regardless of what we do because the record new infections we are seeing will become record hospitalizations. But there are some reasons to be optimistic that we can shorten the really bad period, and make it less bad, if we do the right things.

The Good: The infection reproduction rate, or Rt, was 1.06 this week, down from 1.20 the week before. This is my glimmer of hope. To be clear, 1.06 is still too high. Anything above 1.0 means the number of active infections will continue to rise, and they're already at an unsustainable level. But COVID goes in waves, and the significant drop in Rt means we may be reaching the crest of this particular wave. I already noted that the pace of new infections is leveling off in the KC area. In Lawrence, it has actually begun to go down in the past week. That's what we need to see in the whole state. Both KC and Lawrence have mandated masks for months, and have occasionally taken other measures, like closing bars or limiting their hours. Some people think this is a coincidence. I obviously do not. Gov. Kelly issued a second mask mandate this week, but, like the first one, counties will be able to opt out of it, per the Legislature's orders. I hope that most won't. Based on this heat map, the part of the state that is now seeing the most new cases per capita is western Kansas, where most counties have no mask rules.

The Bad: The test positivity rate in Kansas last week was 35.1%, according to Johns Hopkins. On it's face, that is a really bad number. But again, it's important to see it in the context of where we've been: It was 58.7% the week before. So although we're still confirming more cases, we're also testing more. Which means we aren't missing as many cases. Which is an important step in getting this thing under control.

The Ugly: ICU capacity statewide fell to 30% this week, according to KDHE, including another record-high 279 COVID-19 patients in ICU (which means more than 1/4th of the state's total ICU beds are occupied by COVID patients). And it's actually worse than that. KDHE's data, in the spirit of good old government efficiency, is reported by hospitals to the feds, who then feed it into a computer program and send it back to the states. By the time it gets out to the public, conditions have changed. And it also includes pediatric ICU beds in children's hospitals. Fortunately, the Kansas Hospital Association is now publishing its own data directly. It shows that as of Friday only 16% of staffed adult ICU beds in Kansas were available (including one single bed in all of southwest Kansas). This is a major problem, given that our COVID wave is still peaking and flu season has barely begun. December is when influenza usually starts in earnest in Kansas. Which means that as bad as things are for hospitals now, they're about to get worse. November 2020 will go down in history as the month Kansas hospitals were pushed to the breaking point. Barring a miracle, December will go down as the month when they were pushed past it.

Bonus: Let me start off this section by saying that Kansas House Speaker Ron Ryckman did read my open letter and called me to discuss it. He deserves credit for responding, and his response shows the power each of us have in state level politics. You can find your elected representatives, and their contact info, on this site: http://www.kslegislature.org/li/. I highly recommend you let them know how you're feeling.

I'm not going to get into the details of my conversation with Speaker Ryckman because he asked me not to. But I will summarize it by saying that although he believes in wearing masks, he doesn't think mandating them would work, because Kansans don't like the government telling them what to do. In a certain sense, I agree: another mandate from a Democratic governor, like Laura Kelly, probably is not going to move the needle much in parts of the state that are overwhelmingly Republican, because masks have unfortunately become a political litmus test. I still think that a mandate strongly and publicly supported by a bipartisan group that included Ryckman and other Republican leaders would increase mask wearing. I wish that would happen. But it doesn't look likely, and even if it happened today, our hospitals would still be in trouble for the next couple weeks. So what's a family to do?

My suggestion: hunker down. Limit the time you spend out of the house and avoid interactions with anyone who doesn't live in your house. That means:

- Work from home if you possibly can. Tell your employer it's what the CDC recommends. If your job doesn't allow you to work from home, I'm sorry. The rest of us should do our best to make it safer for you to work.

- Don't travel: I know, I miss my family too, and I want to be with them on Thanksgiving. But it's not worth killing Grandma. Even if you're not concerned about COVID (for instance, if you've already had it and now have antibodies), there are large stretches of Kansas where, if you get in a serious car wreck now, you may not be able to get the care you need promptly.

- If you see friends, do it outdoors, at a safe distance. I know it's cold. Wear a coat.

- Get groceries and other necessities delivered, or pick them up curbside.

- Support local restaurants with takeout or delivery (and leave big tips). Don't risk eating inside.

- Work out at home, but continue paying your gym dues, if you can, to support the employees.

- Don't go to the bar (Congress should get off its collective ass and pay these businesses to stay closed in high-COVID areas, which is frankly most of the country now).

- Manage your chronic conditions: Some hospitalizations are unavoidable (heart attacks, stroke, etc). But it's in your best interest now more than ever to stay out of the hospital if you can. Take your medications, exercise, eat right, get enough sleep, and stay in touch with your primary care doctor via phone, email or telemedicine.

- Get a flu shot: You should have already gotten one, but it's not too late. If you're not comfortable going to a doctor's office right now, get it at a pharmacy.

- Buy a pulse oximeter: If you get COVID, you will be told to stay home, isolate and try to fight it off unless your condition worsens to the point where you absolutely need to go the hospital. This device, which clips on your finger and retails for about $20, will tell you if you've reached that point. It measures your blood oxygen level, and a general rule of thumb is that if that goes down to 90% or below, you should go to the hospital.

That's the best advice I have. Like I said, we're in the bad times now. As Pres. Lincoln once said, "This too shall pass." If we all do the right things, diligently and consistently, it will pass more quickly.

Sunday, November 15, 2020

Kansas COVID-19 Update, Week 18

Kansas descended further into the danger zone this week, as evidence mounted that our health care system is already struggling under the weight of COVID-19, with infections still climbing rapidly. Several of the state's largest hospitals, including Stormont Vail in Topeka and the University of Kansas Hospital in KCK, have now suspended elective procedures and put their "surge" plans in place, adding ICU beds for the crush of new patients. But the health care workforce is already overextended and with record numbers of new infections this week, no matter what we do, it's likely that some people who would have otherwise survived COVID-19 are going to die from lack of timely treatment. But that doesn't mean we shouldn't try to do something. If you're a train conductor and you see that there's another train on the tracks ahead of you, you apply the brake as quickly as you can. Even if you know you won't be able to stop in time to prevent a collision, you want to limit the number of train cars you end up plowing through.

The Good: The infection reproduction rate, or Rt, ticked down ever so slightly last week, from 1.22 to 1.20. That's not enough to prevent catastrophe, given our current rate of new infections. But at least it's trending in the right direction.

The Bad: ICU availabilty, as reported to KDHE by the federal government, was about 34% as of Nov. 12, or about the same as the week before. But that data seems incomplete, in part because while hospitals may be certified for that many beds, they may not have enough healthy staff for that many beds (health care workers are getting COVID too). The Kansas Hospital Association reported that as of Nov. 13, only 20% of staffed ICU beds were available statewide, and only 10% were available in the KC area. Regardless of which dataset you look at, we're at new record highs for COVID-19 patients in ICU (211 as reported to KDHE and 232 as reported by the hospital association). With more arriving every day. More than 20% of our ICU beds statewide are now taken up by COVID-19 patients, which is daunting considering we often exceed 80% of ICU capacity during flu season, even in non-pandemic years. Please pray for our health care workers, and do everything you can to support them in the coming weeks. Their physical and mental health are going to be severely taxed.

The Ugly: Test positivity in Kansas rose to 58.7% last week according to Johns Hopkins, second-worst in the nation behind South Dakota. That's absurd.

Bonus: Bonus content this week is an open letter to Ron Ryckman, a state representative from Olathe who is the Speaker of the Kansas House of Representatives. His email is ron.ryckman@house.ks.gov if you would like to write him too.

Dear Speaker Ryckman,

Like many Kansans, I read that you were hospitalized for about a week in July because of what must have been a relatively serious case of COVID-19. I was glad to hear that you were discharged with a clean bill of health and hope your recovery has gone smoothly since.

I don't know where you were hospitalized, but based on what I know about our hospitals here in Kansas City, no matter where it was, you probably got excellent care. And though I don't know you well personally, I know you well enough to believe that you sincerely want every Kansan to receive the same level of care. I'm writing to you because, by all accounts, we are approaching a point where that will no longer be possible and you, perhaps more than anyone else in the state, have the power and influence to do something about it.

You are a Republican leader who represents eastern Kansas, has roots in western Kansas, and can speak firsthand to the experience of being hospitalized with COVID. That is unique, and perhaps gives you the ability to convince your colleagues that we must change our current approach or our hospitals will be overwhelmed. (If you have kept in touch with any of the people who treated you in July, please ask them what things are like in their hospital today.)

A statewide mask mandate would be the most obvious thing to do, with the least negative consequences, practically speaking. You probably have heard people say that masks don't work (Lord knows I have). Fortunately, there is much evidence to the contrary. The CDC's mask recommendation is based on 45 different studies.

There's evidence that masks reduce transmission of COVID-19 among people who live in the same state.

There's evidence that masks reduce transmission of COVID-19 among people who live in the same community.

There's evidence that masks reduce transmission of COVID-19 among people who live on the same ship.

There's even evidence that masks reduce transmission of COVID-19 among people who live in the same house.

There's also evidence that mask material reduced transmission of COVID-19 among hamsters in cages who were intentionally exposed to the coronavirus (an experiment that we can't do ethically on humans, but is useful because it stripped away all other possible explanations for the reduction in transmission).

I was heartened to see legislative leaders recently agree to something regarding masks: a $1.5 million allocation to the state hospital association for a public service announcement campaign. But this seems insufficient. By the time the PSA is produced and broadcast, our hospitals may already be full. And it doesn't seem like mask compliance is a matter of public awareness at this point. Most people are aware that health officials recommend wearing masks. Unfortunately there is a partisan divide in attitudes toward masks. A bipartisan mask mandate would send a powerful message that masks are not political, but rather just a tool to help Kansans protect each other.

I'm well aware that pushing for a mask mandate would put you crosswise with some of your colleagues. But I believe the politics of mask mandates is shifting fast as hospitals fill up. In just the last few weeks, very conservative leaders in extremely red states like Iowa, North Dakota, Utah and West Virginia have all enacted new mask requirements.

Several of them also enacted new restrictions on gathering sizes, winter sports, and hours of operation for bars. Based on the epidemiological curve of COVID spread, we're only a few weeks behind those states in terms of hospital strain. No doubt many epidemiologists would recommend we take the same measures as them, and more. But at a minimum, shouldn't we do what has little-to-no negative practical consequences: require masks?

Think back to when you were in the hospital in July, probably on supplemental oxygen, since that is generally the benchmark for when a COVID-19 case requires hospitalization. But this time imagine that instead of being in a room, you're in a bed in a hospital hallway or an overcrowded emergency department. Imagine that even with an oxygen mask on, you start to find it difficult to catch your breath (a terrifying experience I'm unfortunately personally familiar with). Imagine that you're mashing the nurse call light, trying to get someone to help you, but no one comes. You can see medical personnel rushing around, tending to other people who are coding even as you grow more and more lightheaded yourself. But there just aren't enough of them.

This is what we're heading for unless we do something to change our current trajectory.

Sincerely,

Andy Marso

Saturday, November 7, 2020

Kansas COVID-19 Update, Week 17

We're in a depressing phase of the COVID-19 pandemic in Kansas: record new cases, record hospitalizations, record ICU admissions and hospitals now under daily, ongoing strain. The novel coronavirus is circulating widely through nearly every corner of the state and the vast majority of our residents still have no immunity to it. It's like a fire that will continue to burn out of control unless we starve it of fuel by staying home as much as possible, staying away from other people when we leave home and wearing masks (made of several layers of fabric, over our mouths AND noses) whenever we are indoors with other people.

The Neutral: The infection reproduction rate, or Rt, is still estimated at 1.22, with a bottom-range possibility of 0.94 and a top-range possibility of 1.45. It's good that it didn't go up, but cases are so widespread now that anything above 1.0 really creates a damaging number of new infections.

The Bad: ICU availability in the state was officially down to 33% on Nov. 5, and it's functionally lower (potentially much lower). As I wrote last week, hospitals (including KU, the biggest in the state) are opening overflow ICU beds because of the influx of patients. That has increased the total number of beds in the state past 1,100, but the problem, like I wrote last week, is that it's difficult to staff those beds. For example, at one point last week there were 32 open ICU beds across most of Kansas City, but only 22 that were actually staffed. Meanwhile, we keep setting new records for COVID-19 patients who need ICU care. Three weeks ago, the record was 128. This week we hit 183.

The strain is being felt throughout the state. In Topeka, a destination for severely ill patients from a wide range of surrounding rural counties, there was only one available ICU bed at one point last week. As the county health officer pointed out, that means that if there had been a single serious auto wreck on Interstate-70 that day, the hospitals probably wouldn't have been able to handle it. Oh, and Wichita's hospitals actually reached full ICU capacity last week, meaning the same was true for Interstate-35.

We are running out of places to send sick people. Barnes-Jewish in St. Louis, the largest hospital in the bistate region, is also reportedly near capacity and considering suspending elective procedures.

So, even though on paper it looks like we still have more ICU beds, the on-the-ground reality is that the medical system is probably already strained to the point where some patients who would have survived will die because they can't get the attention they need as quickly as they need it. Hospitals can’t just create trained staff out of thin air. When New York City was swamped with COVID-19 in the spring, nurses came from all over the country to help. Now most are desperately needed in their home states. There is no cavalry coming. We are in deep trouble.

The Ugly: Test positivity was up to 37.1% last week, according to Johns Hopkins, the fourth-worst in the country (behind South Dakota, Iowa and Idaho). Which means that we still don't know how bad our current outbreak is because we're missing a lot of cases.

Bonus: I don't know what it will take for Kansans to realize what a fraught position we're now in with this virus. One would think that a county commissioner in Johnson County — which has by far the most robust health care infrastructure in the state — raising the specter of erecting temporary hospitals would be enough to do it. Well, that happened this week.

Commissioner Jim Allen, per the Shawnee Mission Post: “The numbers today are worse than they’ve ever been, and if people don’t take it seriously and these numbers keep going up exponentially we could be building temporary hospitals in Johnson County,” he said. “That’s how serious it is.”

And yet, in that same article the county's public health director says he's getting deluged by hundreds of emails a week urging us to just let the virus run through our population until we reach "herd immunity." That seems profoundly unwise, given that even with some minor mitigation measures in the county, like a mask mandate, our hospitals are already nearly full and COVID-19 is so prevalent that nursing home workers who have tested positive are still being allowed to come to work because there just aren't enough well people to replace them. Trying to reach "herd immunity" without a vaccine is a recipe for nothing but thousands of preventable deaths — and we don't even know how long the immunity would last (recent studies suggest COVID-19 antibodies wane quickly).

There is no reason to give up on trying to slow the spread of this virus. Other countries have done it very successfully; rich countries like Australia, New Zealand and Finland, as well as relatively poor countries like Uruguay, Vietnam and Rwanda. They took different approaches in terms of government intervention, but what they all broadly have in common is that their people listened to the advice of epidemiologists and public health officials and more or less did what they said, either voluntarily or because it was the law.

That's the only path out of months of depressing death in Kansas: listen to the people who have studied infectious diseases their entire lives and do what they say, even if it's hard or inconvenient or ideologically unappealing. With every day that we fail to do that, the path narrows further.

Saturday, October 31, 2020

Kansas COVID-19 Update, Week 16

We're in trouble. The U.S. is setting records for new infections almost daily, creeping up on 100,000 a day. The Midwest has been at the center of the surge and Kansas has not been spared. Public health officials have warned us for months that this would happen – that infections would spread rapidly in the fall and winter, when respiratory illnesses always tend to be worse. They urged us to use the summer months to drive down case counts so that we'd be better prepared. States like Michigan and Minnesota, and certain counties within Kansas, that pursued phased reopening and required residents to wear masks have fared slightly better, with the surge coming later and less dramatically than in places like Wisconsin, Iowa, the Dakotas and western Kansas. But now it's basically a wildfire burning out of control and even people who cleared the brush around their own houses are in danger. Hospitals are filling up in several parts of Kansas and western Missouri, and it's having spillover effects on hospitals in others parts of the state. We could be in for a rough winter.

The Not-yet-bad: ICU availability clocked in at 36% in Kansas on Oct. 29, which isn't bad. But it's a bit of a mirage. Hospitals reported 145 COVID-19 patients in ICU that day, which would have been a record except that they reported 153 the day before. Our previous high was 128 two weeks ago. We blew past that three times this week. So why isn't the percentage of available capacity lower? A couple reasons. There are fewer people in ICU for non-COVID reasons than there were a couple weeks ago, but we can't expect that to last, given that flu season is just starting. And some hospitals, including the largest one in the state, The University of Kansas Hospital, are adding capacity by opening up overflow ICU units. It's obviously good that they're doing that, but staffing overflow units for extended periods of time can mean quality of care suffers. It requires a lot of overtime hours and people get burned out.

The Bad: The infection reproduction rate is way up, to 1.22. This is not surprising. It's up almost all over the country. Last week I wrote that the actual rate was probably closer to the high end of the estimated range (1.29) than it was to the exact estimate of 1.06. Now the top end of the estimated range for Kansas is a dismal 1.45. Even if 1.22 is accurate, that means that every infection, on average, causes 1.22 more. When you're starting from about 1,000 new cases per day (where Kansas is now) you can see how quickly this thing spreads.

The Ugly: Test positivity in Kansas was 33.8% last week according to Johns Hopkins. That is just stunningly high, but somehow only fourth-highest in the country behind South Dakota, Wyoming and Iowa. In summary, we're setting records in Kansas for new confirmed cases, new hospitalizations and new ICU admissions, and we're still missing a significant number of infections based on our test positivity. All the trends are bad.

Bonus: A couple weeks ago Via Christi's hospital in southeast Kansas reached capacity and said it would be reaching out to the chain's other hospitals in Wichita and Manhattan for support and resources. Last week Via Christi's hospital in Wichita said it was nearing capacity and could take no more COVID-19 patients (Wichita's other major hospital, Wesley Medical Center, was 90% full). Wichita is a hospital catchment area for most of western Kansas, where ICU beds are scarce to begin with. Which is how you get this KCUR story about a patient in Kearny County, the far southwest corner of Kansas, who was rapidly dying of COVID-19 and needed an ICU bed and a ventilator, but the nearest available was in Kansas City, a seven-hour drive.

We are all connected, whether we want to be or not, and the actions we take (or don't take) affect the people around us, and then ripple out to the people around them, and so on and so forth. So, please, wear a mask, don't gather in groups, try to keep things ventilated indoors as much as possible, and avoid unnecessary close contact with other people, even if you are wearing masks. Oh, and get a flu shot. It might keep you out of a hospital bed, and there's even some evidence it might reduce your risk of a severe COVID-19 infection.

If 1,000 Americans were dying every day in a war, it would be all any of us were talking about and we would be desperate to change course. We are there now with COVID-19.

Sunday, October 25, 2020

Kansas COVID-19 Update, Week 15

The trends continue to go mostly in the wrong direction in Kansas, with the state setting another record Wednesday for 7-day average of new COVID-19 cases. And it's not just because we're testing more, because the percentage of tests coming back positive continues to rise as well. If you have rising case numbers and rising test positivity you can be fairly certain that you have rising infection rates. It shows in the number of deaths the state has recorded lately, as well.

The Good: It's a little hard to determine how COVID-19 specifically affected our hospital ICUs this week because the data is not coming in correctly from the feds. But the overall capacity looks to have held steady at about 35% most of the week. That's good, but I would very much like to know whether the number of ICU beds taken up by COVID-19 patients remains persistently high, like it was the week before. Hopefully HHS Protect gets that info published again soon.

The Bad: The infection reproduction rate (Rt) is up to 1.06. This was to be expected. The case growth we've seen in the past few weeks, coupled with the continuing rise in test positivity, could only mean that each infection was, on average, leading to more infections than before. In fact, if we were testing more, we would probably find that the Rt is more toward the upper end of the estimated range (1.29). At this point we know well what to do to get Rt down: keep your distance, don't gather in groups (especially indoors), and wear masks whenever you're out in public around other people. But if the large house party I observed across the street is any indication, some people still aren't getting the message.

The Ugly: Test positivity in Kansas is up to 19.9%, according to Johns Hopkins. That's eighth-worst in the country.

Bonus: One of the reasons our ICU capacity is holding steady is that a lot of COVID-19 patients are dying lately. As dark as it sounds, that frees up hospital beds. It took six months for Kansas to record its 500th COVID-19 death, on Sept. 11th. The state has recorded roughly another 500 in the six weeks since then. I know we're all tired of hearing the phrase "grim milestone," but at some point this week, Kansas will top 1,000 COVID-19 deaths, if it hasn't already (KDHE doesn't usually update the death numbers on weekends)(UPDATE: Kansas topped 1,000 deaths on Wednesday, Oct. 28, according to KDHE). According to the Federation of American Scientists, if Kansas were a country, it would have had the 12th-highest per capita COVID-19 death rate in the world during the week that ended Oct. 19 (Missouri would be in the top 10 and North Dakota would be the highest in the world).

My god, I cry so much for North Dakota and the Midwest right now. We are just at the beginning of the wave of deaths that are coming.

— Eric Feigl-Ding (@DrEricDing) October 23, 2020

North Dakota has the highest mortality in the world. Higher than ANY country.

(Analysis by my FAS team. HT @euromaestro). #COVID19 pic.twitter.com/WirlY0o1AQ

It's easy to get lost in these numbers, but we should not forget that each of those deaths was a person with a family and friends who will miss them dearly. One of them was John Hickman, a para-educator at a middle school in Olathe. Paras in the Olathe school district make about $13-14 an hour and Hickman, according to KCTV5, specialized in assisting students with special needs.

We can't prevent all of these deaths, but we can prevent some. Masks work. According to one study released this week, people in states with higher rates of mask use are less likely to know people with symptoms of COVID-19. According to another study, universal mask wearing could save more than 100,000 American lives between now and February. We need to try to get as close as possible to universal masking in Kansas, because at our current rate of deaths, we're going to lose another 1,000 people by February.

Sunday, October 18, 2020

Kansas COVID-19 Update, Week 14

During the three-plus months I've been writing this blog, we've seen some tragic death numbers in states like Florida and Texas when hospitals became swamped with COVID cases. This is the first week that I've truly feared that scenario might be coming to Kansas.

The Good: I can't really find anything good this week. The closest thing is that the infection reproduction rate, or Rt, only rose from 1.01 to 1.02. But that's still the wrong direction and based on the other data I wouldn't be at all surprised if the actual Rt number is higher and we're just not testing enough to find out.

The Bad: Test positivity is up again, now to 17.4%, according to Johns Hopkins. If you want to look for a silver lining there, I guess it would be that it's actually rising even faster in other states, so now Kansas is only ninth-worst in the country rather than fifth-worst. But that's just indicative of how bad things are going elsewhere. The test positivity numbers in the last couple weeks in states like Iowa and South Dakota have been truly appalling.

The Ugly: ICU availability was at 35% on Oct. 15. Now, you might say, "What's ugly about that? It's better than the week before." That's true, but here's the ugly part: we now know that the week before wasn't a one-time spike. We are clearly in a sustained period of high hospitalizations for COVID, including ICU hospitalizations. Prior to last week there was only one day in which Kansas recorded more than 115 COVID-19 patients in ICUs: an isolated spike of 121 on Sept. 24. But from Oct. 8 through Oct. 15 Kansas hospitals reported more than 115 COVID-19 patients in ICU every day, including a new record-high of 128 on Oct. 13. This is not a fluke, or an aberration driven by the unpredictable timing of ICU admissions and discharges. It's a troubling trend.

Bonus: 35% ICU availability sounds OK, but it's not distributed evenly across the state. So I started looking for news stories about Kansas hospitals filling up, and man it didn't take long to find them. This Oct. 13 article from the Pittsburg Morning Sun says that Ascension Via Christi, one of the largest hospitals in southeast Kansas, suspended all elective surgeries because of the surge in COVID-19 patients. It's hard to overstate how serious that is. Tests and procedures are the financial lifeblood of U.S. hospitals because of the way our health care reimbursement system is set up (that's not good for patients, BTW, but that's a complex topic for a different time). So for Via Christi administrators to stop them, it must mean they're very concerned that they soon won't have the beds and/or staff to handle the patient load.

The county health officer said in the article that the situation at Via Christi is made worse because the hospitals it would normally refer patients to in Joplin, Mo., and the Kansas City area are also filling up (since the closure of Mercy Hospital in Fort Scott, there are very few hospital beds between Pittsburg and Olathe, a distance of 110 miles). Indeed, an article in the Kansas City Star said that eight hospitals or stand-alone emergency rooms were not accepting ambulances on Oct. 12 because they were too full to take more patients. The KC metro has an abundance of hospitals and ERs (about 35), so there were still plenty of places in the metro for patients to go. But to have eight on ambulance diversion at one time still suggests a surge of patients like what you might see during peak flu season — and flu season hasn't even started.

It's no wonder that things are getting dicey on the east side of the state, given that both Kansas and Missouri have been reporting their highest seven-day averages of new daily COVID-19 cases of late. This "heat map" shows, in red, U.S. counties with the most new COVID cases per capita during the two weeks leading up to Oct. 15. You'll notice there's a whole lot of red throughout western Missouri.

Those are mostly rural counties without a lot of ICU beds, so many of the sickest patients from those areas will end up in regional hospitals in places like KC. Which can cause hospitals to fill, even if KC area counties themselves are not red.

Another area you might notice has a lot of red is western Kansas. And yes, hospitals are filling up there too. Witness this Associated Press dispatch, in which the sheriff of Gove County gives a somewhat surreal phone interview while struggling to breathe in a hospital bed in Hays. The sheriff (who has since recovered) had COVID-19. So did the county's emergency management director, the CEO of Gove County Medical Center and more than 50 staff members at the medical center. Which was why the sheriff was in Hays, almost an hour away: the local hospital was full.

And yet, based on the AP story, the leaders of Gove County have no intention of requiring people to wear masks. The county commission did require masks briefly in early August, when COVID-19 cases began to spike. But that only lasted 11 days. Then the commissioners caved to public pressure and repealed the rule. Which has to be frustrating for the people of Hays, which is mandating masks while their hospital fills up with patients from other counties. It's clearly frustrating for Tom Moody, a commissioner from Crawford County who said this in the Pittsburg Morning Sun article about Via Christi:

“We’re allowing these other counties that are doing basically nothing (to stop COVID-19) to fill our hospitals, which takes away from our county constituents,” Moody said. “Would it be beneficial if we tried to get a meeting with the other counties to let them know our feelings on this? Because to me it’s bullshit that they’re doing this, and it really upsets me.”

This was an entirely predictable outcome of the Kansas Legislature undercutting Gov. Laura Kelly's COVID-19 orders and leaving it to each city and county to decide what measures they will or won't take to stop COVID-19 (and Gov. Mike Parson doing the same in Missouri). It's a virus, so it doesn't respect county borders. And most ICU beds are located in urban areas that are requiring virus mitigation measures, so they're going to take the sickest patients, even if they come from counties that aren't enacting any mitigation measures.

Since the early days of the pandemic some political leaders have advocated a very light-touch approach from government, saying that citizens will voluntarily do the right things to protect each other. But there's a lot of evidence that's just not true, whether it's articles about people being openly hostile to businesses that try to require masks, or even threatening to kidnap and kill political leaders who support mask rules.

Masks work. They are not a panacea, but they have been shown to reduce the daily growth rate of COVID-19 infections by 40%. Kansas could use every bit of that 40% as we try to keep our hospitals from filling up. The next month will be critical.

As Chris Christie said earlier this month after barely surviving COVID-19:

“Every public official, regardless of party or position, should advocate for every American to wear a mask in public, appropriately socially distance and to wash your hands frequently every day.”

Saturday, October 10, 2020

Kansas COVID-19 Update, Week 13

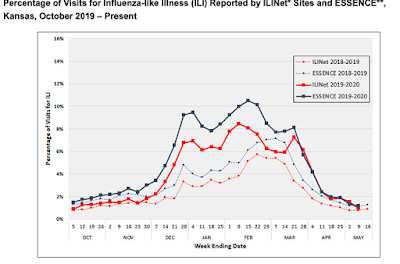

There was another spike in COVID-19 ICU hospitalizations in Kansas this week. It's not quite as high as the one two weeks ago, but still concerning, especially since overall capacity seems to have been more affected this time. Here's the weekly update:

The Good: The infection reproduction rate, or Rt, stayed at an estimated 1.01 this week. It's the third straight week at that number. We would prefer for it to be going down, rather than staying the same. But this is the best I can do in terms of silver linings this week: each infection doesn't seem to be causing more new infections than it did in weeks past. But once you get enough infections out in the community, any Rt number above 1.0 can cause significant problems.

The Bad: One of those problems, eventually, will be overloaded hospitals, which we've previously seen in parts of New York, New Jersey, Michigan, Louisiana, Florida and Texas. We're not there yet in Kansas, but this past week was a step in the wrong direction. Kansas hospitals reported 119 patients in ICU because of COVID-19 on Oct. 8 (with 130 hospitals reporting). That was the second-highest number on record, trailing only the 121 from two weeks earlier. But while that previous spike didn't hurt overall capacity (ostensibly because fewer people were in ICUs for other reasons), this time it did. The percentage of ICU beds available in the state dropped from 37% the week before to 32% on Thursday. That's the lowest it's been since I started checking in early July, and flu season hasn't even started. So get your flu shot before the end of this month, and encourage everyone you know to get it too, unless you or they have a medical condition that precludes vaccination.

The Ugly: It's always test positivity, it seems. It went up again this week, according to Johns Hopkins, rising to 16.2% in Kansas. That was fifth-worst in the nation, behind only Idaho, South Dakota, Wisconsin and Iowa. Twenty states (and DC) are below 5%, so it can be done. But it takes an awful lot of testing.

Bonus: Our bonus this week comes courtesy of documents from the White House Coronavirus Task Force that were leaked to the Center for Public Integrity (don't ask me why the work product of a group of civil servants paid for with taxpayer money needs to be "leaked" to the public rather than just published). Task force documents from Oct. 4 show that the following Kansas counties were deemed in the "red zone" for having high numbers of COVID-19 cases per capita: Ford, Ellis, Finney, Crawford, Seward, Barton, Cherokee, Dickinson, Grant, Franklin, Pottawatomie, Thomas, Rooks, Stevens, Nemaha, Phillips, Cheyenne, Rawlins, Ness, Rush, Logan, Sherman, Sheridan, Gove, Marshall and Scott. That's most of southwest Kansas, a significant chunk of northwest Kansas, most of the area around Hays, a couple counties in southeast Kansas, a couple along the northern border with Nebraska (a state where hospital capacity is starting to become a real problem) and a couple near Fort Riley. The task force recommends that masks be worn in indoor public places throughout the state, but most of those red zone counties are quite rural and don't have any rules about mask wearing. Several urban counties that do have mask mandates fall into the task force's "orange zone" (Wyandotte) or "yellow zone" (Johnson, Sedgwick, Douglas, Shawnee). So masks aren't a panacea. But very few people are claiming that they are. Masks are an evidence-based way to reduce transmission of the novel coronavirus, at little to no cost to the wearer or society at large. Seems like a good trade.

Saturday, October 3, 2020

Kansas COVID-19 Update, Week 12

Obviously, it's been quite a week for COVID. With everything happening in DC, the news looks pretty mundane here in Kansas, but it's still worth keeping an eye on how things are going closer to home.

The Good: Last week we saw COVID-19 cases in Kansas ICUs rise to a record 121. This week that figure was down to 103, which is still a tad high but largely in line with where it's been the last few months. It should be noted, though, that only 120 hospitals reported data this week, as opposed to 130 last week. But available ICU capacity remained almost unchanged at 37% (as opposed to 36% last week). ICU numbers can fluctuate a lot from day to day, or even within the same day. People get better and are discharged from ICU, people get worse and are admitted to ICU, people in ICU pass away. So it's important to focus on the long-term trend, rather than just one data point. Right now, that trend still looks pretty stable (but a bit high).

The Neutral: The estimated infection reproduction rate, or Rt, is unchanged from last week at 1.01 in Kansas. Interestingly, though, the folks who calculate it on the site I use have reduced the low end of the possible range from 0.80 to 0.77 (while leaving the high end at 1.21). That seems like a good sign, potentially.

The Ugly: Test positivity rose again last week to 15.9%, according to Johns Hopkins. That's seventh-worst in the nation, ahead of only Mississippi, South Dakota, Idaho, Wisconsin, Iowa and Missouri. Remember, when test positivity is above 5%, there's a good chance you're missing a lot of COVID-19 cases. Which of course makes tracing and isolating cases impossible and creates a "silent spread."

Bonus: This week's bonus comes from the blog (self-promotional, I know). It's a satirical homage to the idea that it's not the government's place to enact any COVID-19 restrictions.

We should have no COVID-19 restrictions... or traffic restrictions

Author's note: This is satire. I don't actually believe any of this. I'd like to think that I don't truly have to explain that, but... that's kind of where we are now.

I’ve been listening to people who are against any government restrictions related to COVID-19 for several months now and, I gotta say, they’re starting to make a lot of sense. In fact, based on their arguments, I’ve come to an important conclusion: we must immediately repeal all traffic laws.

It’s become clear to me that these “rules of the road” are really just another example of egregious, nanny-state government overreach. By tolerating them, we as citizens have just moved, like willing sheep, one step closer to welcoming tyranny.

We must protect our right to drive the way we want to drive. The government should get out of the way and let everyone choose their own level of risk. If you want to stop at every red light or stop sign, fine. But I refuse to live in fear.

For years now we’ve been warned about the dangers of reckless driving. But did you know that only about 40,000 people in the U.S. die in traffic accidents every year? That’s about the same as the flu, and we don’t make people follow a bunch of rules just to prevent the flu.

Besides, the car wreck death count is obviously overinflated. How many of those people had other medical conditions, like obesity, at the time of the crash? A lot of them were probably going to die anyway. I bet doctors are just writing “car accident” on death certificates so they can get kickbacks from trial lawyers who are looking for big paydays suing auto insurance companies. My friend’s co-worker’s uncle knows a nurse who said she saw that happen once.

Most car wrecks aren’t even serious. I bet you didn’t know that, because the fear mongers in the media never show you the thousands of wrecks that are just harmless fender-benders. They concentrate only on the few here and there that end in violent dismemberment and death. So cynical.

Now the “morality police” (and also the actual police) keep telling me I have to wear a seatbelt. I can hardly get in a car with other people without them telling me to put it on. One time I even got pulled over by a cop who warned me that the next time I drove without a seatbelt I might get a ticket. I mean, is this America, or Soviet Russia?

I don’t believe in seatbelts anyway. Sure, a bunch of “experts” say they have “studies” that show they save lives. But where were all those experts in the 1950s? We had cars then, but no seatbelts. And some people who wear seatbelts now still die in car crashes. Really makes you think. Whenever I try to wear a seatbelt it feels like I can't breathe. That's probably the real danger: getting strangled by your seatbelt.

And what’s with all these capacity laws? How is the government going to tell me that I can’t put 11 people in my subcompact car, when there are vans and buses all over the road carrying way more people? How is one safe, but not the other?

Anyway, I’m done listening to the government or blindly trusting the “experts.” If cars had some kind of potentially debilitating condition that they could spread to other cars just by getting close to them, then maybe we would actually need traffic laws. But right now, I just don’t see it.

Saturday, September 26, 2020

Kansas COVID-19, Week 11

Last week we saw a dip in ICU capacity that was NOT due to more COVID-19 cases, but to other types of hospitalizations. This week the capacity is nearly unchanged, but the amount taken up by COVID-19 cases is up sharply. That's not only disturbing, but a good reminder to look at the data behind the data whenever possible.

The Good: The infection reproduction rate, or Rt, has dropped to 1.01, which is just barely above the level at which the raw number of infections should start trending downwards — if that number is accurate. Unfortunately, due to the lack of testing in Kansas, it's hard to tell how accurate it is. The site I use to track Rt says its best estimate for Kansas is 1.01, it also says that the true number could be anywhere between 0.80 to 1.21. More testing would help narrow that range.

The Bad: As of Sept. 17, the state's hospitals had 36% of their ICU capacity free (with 130 hospitals reporting data). Of the 623 patients in ICU on that day, only 80 were in because of COVID-19. As of Sept. 24, the state again had 36% ICU capacity remaining (with 128 hospitals reporting). But — and here's where the bad part comes in — of the 632 total ICU patients on that day, 121 were in because of COVID-19. That's the largest number since the state started keeping track (the previous high was 112 on July 21). That doesn't bode well. Let's hope it's a blip and not a trend.

The Ugly: Test positivity in Kansas was 15.4% over the last two weeks. That's up a tad from last week (15.1%). This is way too high and it means we're probably missing a significant number of cases. It also means that if the Rt above is off, then the actual number is probably higher.

Bonus: The bonus section is back this week because I want to share another useful website. It's called the Daily Yonder and it's published by the Center for Rural Strategies. The cool part is a county-by-county map that controls for population to show which counties have more than 100 new COVID-19 cases a week per 100,000 people — the White House Coronavirus Task Force's "red zone" threshold. It shows that in Kansas, as in most states, rural areas have not been entirely spared. Some rural areas, like a strip of counties along the northeast border with Nebraska and another strip along the south-central border with Oklahoma, have little COVID-19 per capita. But rural counties in the southwest corner, southeast corner and the center of the state around Hays are all in the red zone. Urban counties are a similarly mixed bag, with low levels of COVID-19 per capita around the Topeka and Wichita metro areas, but relatively high levels around the Kansas City metro. There's nothing magical about the 100 new cases per 100,000 threshold, but the map is a good way to visualize which parts of the site have more than their share of COVID-19, and are therefore disproportionately driving the statewide numbers.